October 2, 2018 PAP-Q3-18-NI-006

Patient centricity should not stop at clinical trials. There is mounting evidence that positive outcomes increase when patients are considered throughout the process of drug product development.1 Although individual patient needs are often disparate, there are many similarities that unite patient groups. One of the most effective ways to address patient centricity in manufacturing is with dosage form implementation and design. Drug manufacturers often default to traditional formulations, though a creative alternative might drive overall patient adherence — as well as satisfaction. Taking the needs of the patient into consideration when designing a formulation would likely result in a host of benefits, from a decrease in medication errors and adverse incidents to an overall improvement in treatment outcomes, as well as a means to increase cost savings.1

The FDA has formally recognized how crucial the patient’s voice is to the industry. To put this into practice, the FDA conducted 24 disease-specific, patient-focused drug development (PFDD) meetings in order to hear about patient concerns, experiences, perspectives and treatment options. These findings were compiled in a series of reports known as the Voice of the Patient, and are all available to the public.2 According to the FDA, “Patient-focused drug development (PFDD) is a systematic approach to help ensure that patients’ experiences, perspectives, needs, and priorities are captured and meaningfully incorporated into drug development and evaluation.”3 The FDA recognizes that patients are in a position to contribute key information to drug developers, as they are experts on living with the disease and can provide insight into therapies.3

The FDA will develop guidances based on patient experience data, with that data applied in relation to drug development. The guidances will be released over a five-year period, having started in Q4 2017 and slated until Q4 2021 under Title III of the 21st Century Cures Act.4 The goal of these guidances is to better inform the FDA, patient stakeholders, researchers and regulated industry in order to develop more effective therapies that respond to overall patient needs, as they have been self-identified.4 The FDA is focusing on patient-focused drug development in order to meet the following goals, according to FDA.gov:3

Although the FDA is encouraging patient centricity in drug development through this series of guidances, there is not a single, approved definition on patient-centric drug development and design.5 Until a uniform definition is established, there is room for confusion, misinterpretation and error. “To stimulate scientific research and discussions and the consistent interpretation of test results, it is essential that such a definition is established,” noted a whitepaper on the subject, titled “Defining Patient Centric Pharmaceutical Drug Product Design.” Of particular concern are the growing elderly and multi-morbid populations, who are akin to pediatric groups in their limitations. For these patients, managing medication is an overwhelming task, with consequences that can be serious.5

Drug developers must take patient diagnosis and ability into context when creating a drug; for instance, a patient who suffers from a manual dexterity impairment may have difficulty opening a traditional oral solid dose prescription bottle or breaking a tablet.5 Taking this into context, drug developers cannot forget their target patient populations when formulating a drug. A drug should not be designed solely around the API or what makes best sense chemically, when the dosage form may actually pose a tremendous barrier of access to the patient for whom the drug was supposedly designed.

According to the whitepaper authors, “patient centric pharmaceutical drug product design” should be defined as “an approach that directly aligns product characteristics with patient characteristics for a therapeutic goal in a targeted patient population(s), and requires an appropriate definition that can be used consistently among key stakeholders.”5 User behavior must be considered as soon as a drug is created for it to be effective, and patient ability should be embedded in the drug’s design and production. Drug products that are truly patient centric will reduce the likelihood of errors in adherence and improve a medicine’s overall effectiveness. Formulations must take the patient’s environment and experience into account to confirm that the medicine adequately addresses patient needs.5

A market study on dosage forms, which polled U.S. and German respondents, cited that about half of the population had problems swallowing tablets — because they either were too big or became stuck in the throat. The result was interference or nonadherence.6 According to the survey, “23% reported breaking tablets before swallowing, while another 14% crushed and dissolved them in water in order to swallow them. A full 10% stopped taking their medication entirely, while 9% looked to a different dosage form altogether.”6 The survey also polled respondents on positive qualities of oral solid dosage forms. Swallowability was overwhelmingly an issue. According to the study, nearly two-thirds of the U.S. participants (66%) reported that their medicine should be easy and comfortable to swallow, 38% coded a pleasant taste or odor as important, while 34% assigned significance to a product that is able to easily integrate into their lives.6

This opens up the potential for pharmaceutical innovation and for drug developers to think beyond traditional tableting. Awareness of other dosage forms does not seem to be an issue. Alternative options that scored high on awareness include chewables, known to 90% of the U.S. population, effervescent tablets or lozenges, which captured 85% of awareness and instant drinks (80%).6 These are alternatives to the traditional methods of drug delivery that the population is already familiar with and indicates a preference for. More than 60% of U.S. participants have already imbibed both chewable tablets and lozenges. Traditional tablets and capsules scored lower on characteristics such as “ease of swallowing, sensation in the mouth, package opening, and ease of intake” than alternative user-friendly dosage forms.6

Can patient centricity also apply to parenteral dosage forms? The difficult-to-administer dosage option has become the default method of biologics — which are increasingly gaining traction in the public sphere and in the industry. In order to incorporate patient centricity into sterile dosage forms, the product has to be reviewed. “Overall design of the premixed fill, package material, and the functional attributes of the IV bag are integral to patient-centric product strategies,” Marga Viñes, Business Development Manager, and Oriol Prat, Director of Contract Manufacturing at Grifols, wrote in Pharma’s Almanac in 2016.7 Issues with parenterals are also more likely to occur when there are multiple steps involved, even within a hospital setting. “The more complicated the solution, the greater the margin for error,” wrote Viñes and Prat. Issues with improperly administering the correct dosage forms have also led to patient deaths. According to a five-year FDA study, “the most common medical errors resulting in patient death were administering an improper dose.”7 As an alternative, the company offers premixed solutions available in flexible plastic bags, which deliver a fixed dose. The bags are terminally sterilized so that safety is assured. “Another example of the benefits of premixture versus admixture delivery strategies is that reasonable dosage limits are likely to encourage healthcare providers to write more cost-effective orders,” they also noted.7

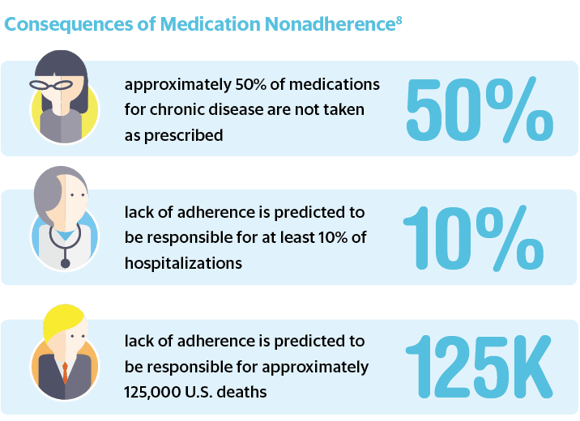

The cost of nonadherence, regardless of dosage form, is high. Nonadherence places an estimated $100–289 billion burden annually on the U.S. healthcare system.8 It is also common — approximately 20–30% of prescriptions are never filled, and approximately 50% of medications for chronic disease are not taken as prescribed.8 This lack of adherence is believed to be responsible for approximately 125,000 U.S. deaths, at least 10% of hospitalizations and an increase in morbidity and mortality.8 Adherence is a complex issue, affected by patient behavior and a range of demographics, from social and economic influences to individual beliefs and access to care.8 “There are so many reasons patients don’t adhere — the prescription may be too complicated, they get confused, they don’t have symptoms, they don’t like the side effects, they can’t pay for the drug, or they believe it’s a sign of weakness to need medication,” Dr. William Shrank, chief medical officer at the University of Pittsburgh Health Plan, told The New York Times.9 “This is why it’s so hard to fix the problem — any measure we try only addresses one factor.”9 However, since these barriers have been identified, they can now be factored into drug design — the solution to this nationwide crisis must begin with the manufacturing and development organizations.

The dialogue around patient centricity has penetrated all aspects of the industry. It is not enough to design a drug that works; developers must consider what works for patients and how this design will be adopted in a real-world context. Taking on a non-isolated and patient-centric approach to drug development will integrate patient demands into design and thus help to assuage the nonadherence epidemic in pharma, while lowering cost burdens and increasing patient outcomes. The drug manufacturer that can fully understand this need and implement patient centricity into production is likely to come out ahead of the competition.

David is Scientific Editor in Chief of the Pharma’s Almanac content enterprise, responsible for directing and generating industry, scientific and research-based content, including client-owned strategic content, in addition to serving as Scientific Research Director for That's Nice. Before joining That’s Nice, David served as a scientific editor for the multidisciplinary scientific journal Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. He received a B.A. in Biology from New York University in 1999 and a Ph.D. in Genetics and Development from Columbia University in 2008.